China’s decision to cap beef imports has put Brazilian meatpackers through an unusually demanding test of commercial — and strategic — maturity.

While heavy reliance on China exposes a structural vulnerability for exporters, the global beef market is exceptionally tight, leaving Brazil better positioned than most peers to absorb the shock and adjust.

To navigate Beijing’s safeguards, exporters will need to carefully pace shipments under the annual quota, seeking to preserve long-term leverage with Chinese buyers while safeguarding the economic balance of the cattle supply chain at home.

That requires avoiding short-term, price-disruptive behavior that could destabilize the livestock market, according to people involved in industry discussions. A rush to exhaust quotas as quickly as possible is widely seen as the worst possible outcome, which is likely to push cattle prices sharply higher at first, only to trigger a subsequent slump.

“We don’t want to make a lot of money very fast by breaking the supplier,” one exporter said.

Executing such restraint, however, is far from simple. Export prices to China have already climbed more than 15%, surpassing $6,000 per metric ton after the quotas were announced — a dynamic that could easily tempt packers into chasing volumes.

Patience, industry executives say, will be critical, even if it means weaker financial results this year. While Brazil has diversified its export destinations in recent years, there is still no true substitute for China’s scale.

Beef Flow Set to Shift

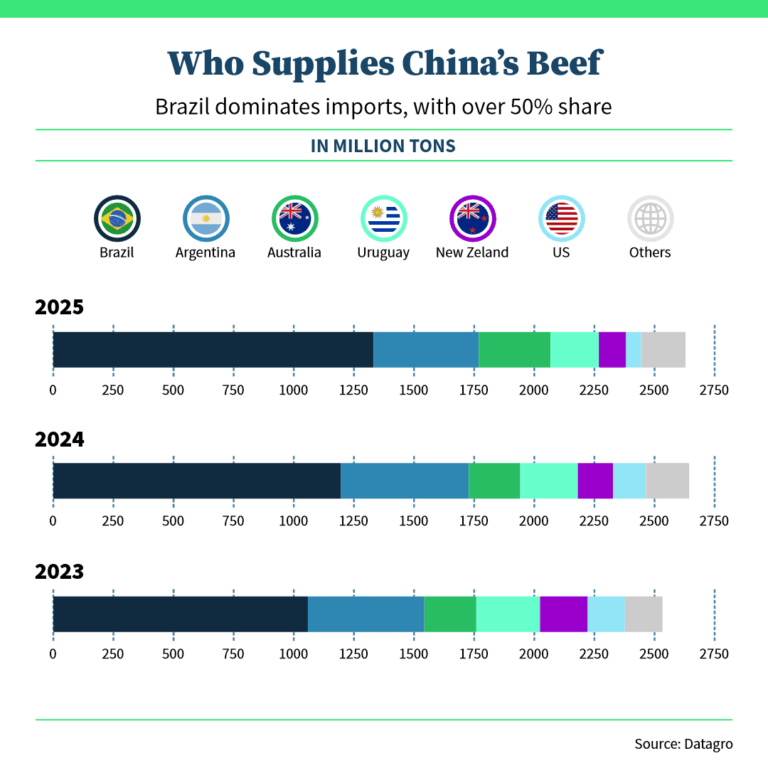

Estimates from consultancy Datagro suggest that between 400,000 and 600,000 metric tons of beef may need to be redirected to other markets. That is equivalent to roughly 3 million head of cattle — a near-term shock, but one Brazil is better equipped to manage thanks to tight global supply and the competitiveness of its herd.

The United States has emerged as a key alternative destination after reopening its market to Brazilian beef. Although product specifications differ — U.S. imports are typically leaner cuts used for ground beef — part of the volume originally earmarked for China is expected to flow there.

Regional dynamics may further amplify arbitrage opportunities. Argentina and Uruguay, which received more generous Chinese quotas, are likely to divert more of their domestic production to China, potentially sourcing additional beef from Brazil to fill gaps elsewhere. That creates advantages for companies with multi-country operations across South America.

Over time, China itself may feel the effects of constrained Brazilian supply. If packers spread shipments evenly across the year, China would still be importing less than its effective demand — a gap that domestic production is unlikely to close.

Last year, Brazil shipped nearly 1.7 million metric tons of beef to China, accounting for more than half of the country’s imports. Even allowing for some front-loaded buying ahead of the safeguards, consumption levels remain well above the new quota.

Industry executives expect that reality to reassert itself over the medium term. If other exporters fail to fully utilize their quotas, China could ultimately loosen restrictions and reallocate unused volumes — a possibility already hinted at by Brazilian officials.

For now, exporters see restraint as the only viable strategy. Recent trade disputes — from U.S. tariffs to tensions with major European retailers — suggest Brazil’s meat industry has learned that, in tight global markets, discipline can be as valuable as speed.