Brazil is weighing a cut in ethanol import duties in return for lower U.S. tariffs on beef and coffee — a move that could squeeze local producers already facing weak prices.

No date has been set for the next round of trade talks between Brazil and the U.S., but signs are emerging of what each side wants — and what Brazil may be willing to give in.

For the Brazilian government, the top priority is to secure lower U.S. tariffs on beef and coffee, both subject to a 50% tariff and among the country’s key exports to the American market. Ethanol, meanwhile, could serve as a bargaining chip in the negotiations, raising concern among domestic producers.

U.S. ethanol currently faces an 18% import tariff in Brazil — a levy the White House calls “unfair” and has targeted in a trade probe launched in July.

People familiar with the talks told The AgriBiz the Brazilian government appears ready to yield on this point. “There’s no longer any question whether the government will give in — only how and when,” one source said.

A tariff exemption would be good news for U.S. producers grappling with oversupply. Record corn harvests have driven ethanol output to new highs, pressuring domestic prices. Roughly one-third of the U.S. corn crop is used for ethanol.

“Still, exports to Brazil would not solve their problem. U.S. ethanol surplus is estimated at 8 billion liters,” said Willian Hernandez, a partner at FGA consultancy. The largest volume the US has ever shipped to Brazil was 2 billion liters.

In Brazil, traders and analysts warn the move could hurt companies investing to expand production to meet targets set by a local regulation known as “Fuel of the Future”.

“We’ve urged Brazilian diplomats to carefully consider this issue,” said Martinho Ono, a partner at SCA Trading. “Ethanol is part of Brazil’s energy policy — it shouldn’t be used as a bargaining chip. We’ve been adamant that it must not be auctioned off.”

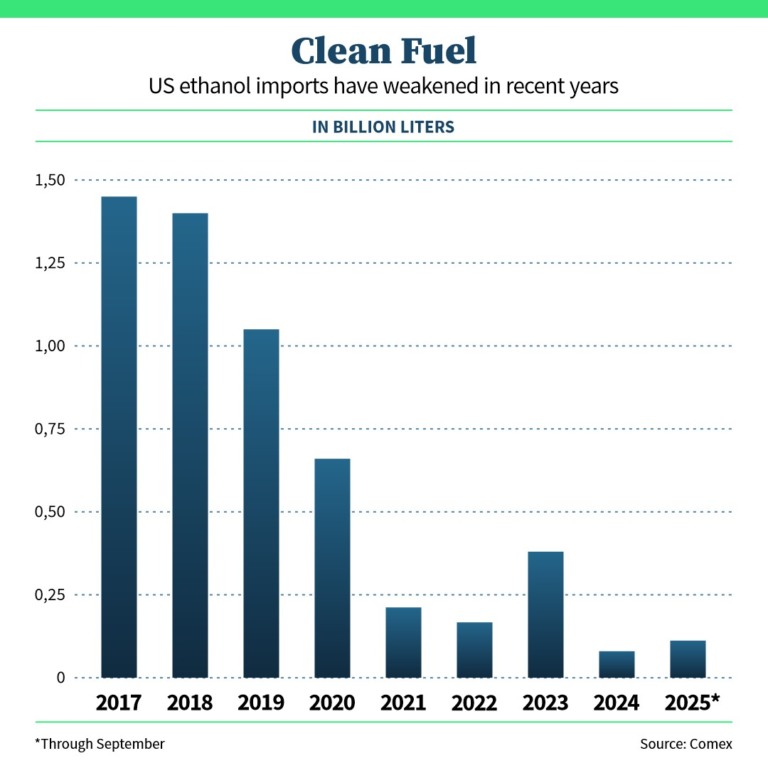

Brazil was once the top export market for U.S. ethanol but introduced tariffs in 2017 after a flood of U.S. product crashed local prices. Imports have since dwindled, limited mostly to off-season windows when U.S. ethanol can compete. The rapid growth of Brazil’s corn-ethanol industry has further reduced the need for foreign supply.

Bad Timing

Local producers fear that an influx of U.S. ethanol could worsen an already difficult outlook for mills, which are expected to face tighter margins next season.

At least three factors should weigh on ethanol and sugar prices in 2026: a recovery in global sugar output; a likely shift by Brazilian mills toward ethanol; and falling gasoline prices, which erode ethanol’s competitiveness. On top of that, Brazil’s corn-ethanol output is projected to jump 20% next year to 10 billion liters.

“The outlook is already bleak for next year, even without imports. Remove the tariff, and it gets worse,” said the SCA director.

He estimates Brazil’s ethanol supply will rise by 3 to 4 billion liters next season as cane yields recover and mills increase the share of ethanol in their production mix. That expansion should push prices lower, narrowing import margins.

“Import arbitrage will naturally shrink. But without tariffs, another major producer enters the market, depressing prices further.”

The potential market share for U.S. ethanol is seen at as much as 10% of total Brazilian demand, Ono said. Brazilian fuel distributors must contract 90% of the anhydrous ethanol they plan to sell a year in advance, under a rule from energy regulator ANP — effectively reserving most of the market for local suppliers.

U.S. producers, who primarily make anhydrous ethanol, also face limits on the segment of Brazil’s market they can serve. That’s because Brazilian flex cars are directly fueled with hydrous ethanol, while anhydrous is mixed to gasoline and represents a smaller portion of the market.

“U.S. producers could adapt their plants in the Midwest to make hydrous ethanol that meets Brazilian specifications, but that would require investment,” Ono said.

Northeast Mills at Risk

Because U.S. ethanol typically enters Brazil through northeastern ports — the closest to the U.S. — industry leaders and politicians fear a wave of imports could hit smaller, less competitive local mills.

The Northeast produces around 2.5 billion liters of ethanol a year and isn’t self-sufficient, making it more vulnerable to imports.

“The shipments arrive during our harvest season, leading to predatory competition that erodes our competitiveness,” said Renato Cunha, president of Novabio, a bioenergy association representing regional mills. “We end up selling below production costs, without adequate returns — and consumers don’t see lower prices.”

The effects wouldn’t stop there, Cunha added. “If the U.S. sends 1 billion liters, as it did when tariffs were zero, the volume is too large to stay contained in one region. Since Brazil doesn’t need imports, U.S. ethanol ends up depressing prices nationwide.”

Brazil, the world’s second-largest ethanol producer, is expected to make about 36 billion liters in the 2024/25 season, while domestic demand is projected at 35 billion liters.

What About Sugar?

Some in the industry argue that if ethanol enters the trade talks, sugar should too. Washington imposes a $360-per-ton duty on Brazilian sugar that exceeds a small 150,000-ton quota shared among 39 countries.

“It’s a very limited quota — and we’re not even the largest holder,” Cunha said. “If any deal is to be made, it should involve trading ATRs [Total Recoverable Sugar] to balance sucrose output.”

Under that scenario, Brazil could import U.S. ethanol duty-free while exporting more sugar to the U.S. under a tariff exemption.

Brazilian negotiators, Ono said, should also highlight the sustainability advantage of cane-based ethanol compared with U.S. corn ethanol. “Our ethanol has a far smaller carbon footprint,” he said.